A slightly sad realization hit us at VirtusLab recently - our "collection" of starred repositories has grown to ridiculous proportions. So we decided to change the approach: every other Wednesday, we pick one trending repo and take it apart piece by piece. This way, we'll understand them better and discover where we can genuinely help.

Today's project dropped on Hacker News frontpage just days ago and instantly sparked one of the most interesting security discussions I've seen in a while. We're looking at Matchlock by Jingkai He - a CLI tool for running AI agents in ephemeral microVMs with network allowlisting and secret injection via MITM proxy. Written primarily in Go, MIT-licensed, and built to answer a question that every developer running claude --dangerously-skip-permissions should be asking: "What's the worst that could happen?"

The Problem Nobody Talks About (Until It's Too Late)

Let's be honest: we've all done it. You fire up Claude Code, Codex, or whatever agent du jour you prefer, and you hand it the keys to your system. --dangerously-skip-permissions - because you trust the model, right? And because adding --dangerously to a flag name is basically a dare.

The uncomfortable truth is that AI agents are adversarial by accident. They don't need to be malicious - they just need to be manipulated. The now-famous PromptArmor demonstration showed how Claude Cowork could be tricked into exfiltrating files through a prompt injection attack. And that's the commercial, polished product with Anthropic's full security team behind it.

Now imagine what happens with your $ANTHROPIC_API_KEY sitting in an environment variable while an agent runs arbitrary code. One rogue curl command - whether triggered by a prompt injection, a hallucinated package, or a compromised dependency - and your credentials are gone. The sandbox solutions that exist today (bubblewrap, basic containers) either don't control network egress, don't work cross-platform, or require a PhD in Linux namespaces to configure properly.

Enter Matchlock.

Architecture: Defense in Depth, Not Defense by Hope

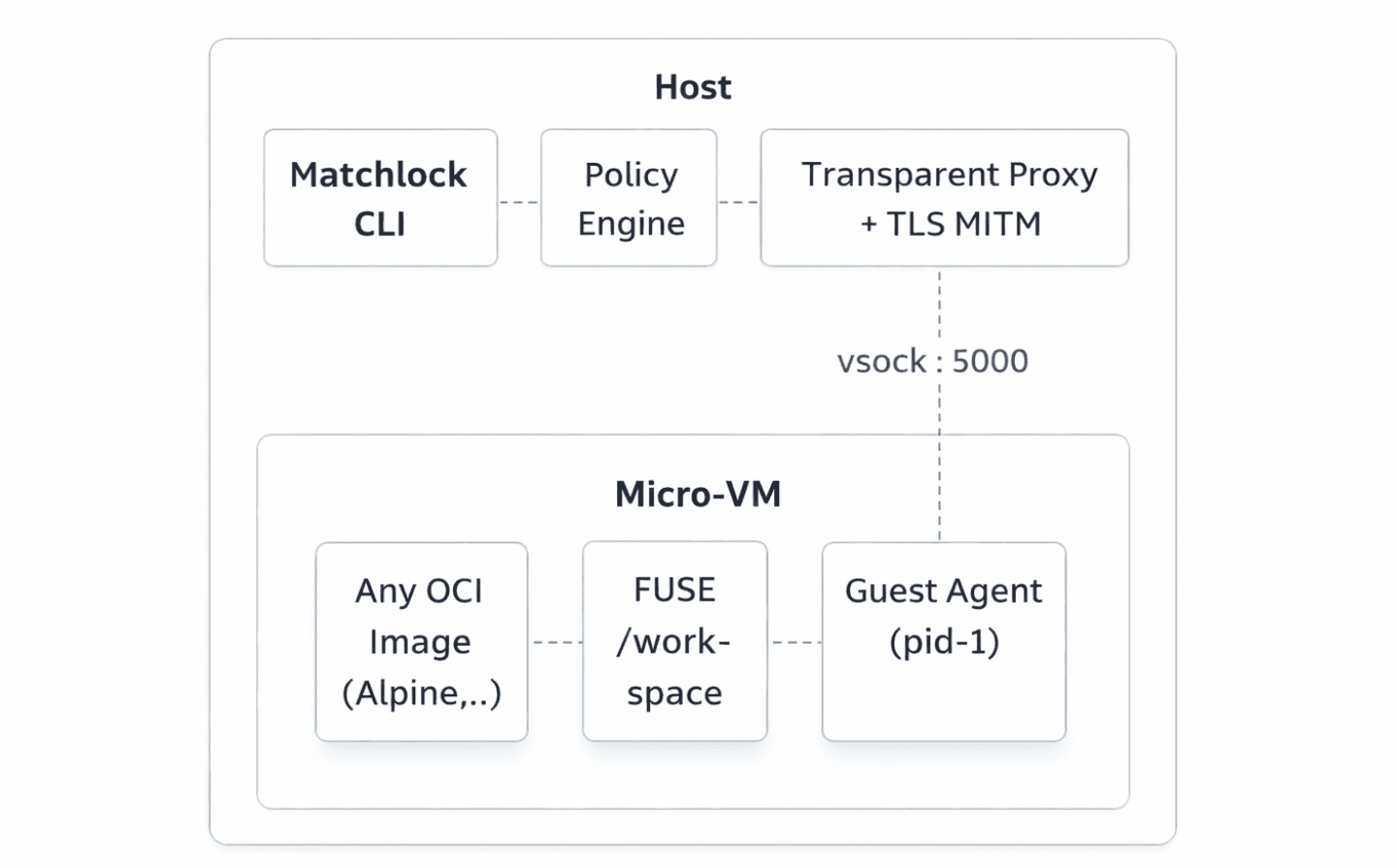

Matchlock's architecture is elegant in its paranoia. Let me walk through the key layers:

Layer 1: The VM Boundary. On Linux, Matchlock launches Firecracker microVMs - the same VMM that powers AWS Lambda. On macOS, it uses Apple's native Virtualization.framework. Both boot in milliseconds. This is not namespace isolation like Docker. This is hardware-level virtualization with its own kernel. A sandbox escape requires a VM breakout, which is an entirely different (and much harder) class of attack than a container escape.

Layer 2: Network Lockdown. Everything is denied by default. No network egress unless you explicitly allowlist a domain with --allow-host. The implementation is platform-specific: on Linux, Matchlock uses nftables DNAT rules to redirect ports 80/443 through its transparent proxy. On macOS, it runs a gVisor-based userspace TCP/IP stack at L4 for traffic interception. This is the layer that would have prevented the PromptArmor-style exfiltration - even if the agent is tricked into sending data, there's nowhere for it to go.

Layer 3: Secret Injection via MITM Proxy. This is where Matchlock gets genuinely clever. When you configure a secret:

The real API key never enters the VM. Inside the sandbox, $ANTHROPIC_API_KEY resolves to a placeholder like SANDBOX_SECRET_a1b2c3d4. When the agent makes an HTTPS request to api.anthropic.com, the host-side transparent proxy performs TLS MITM, intercepts the outgoing request, and swaps the placeholder for the real key - but only for that specific host. If the agent tries to POST the same placeholder to evil-exfil-server.com? The request is blocked at the network layer because it's not on the allowlist. Even if it were allowed, the attacker would only get a useless placeholder string.

This is a fundamentally sound security model. Secrets are scoped to specific domains at the network layer, not the application layer. You can't trick the agent into leaking them because the agent never has them.

Layer 4: In-VM Hardening. The guest agent (running as PID 1) spawns commands in a new PID + mount namespace. In non-privileged mode, it drops capabilities like SYS_PTRACE and SYS_ADMIN, sets no_new_privs, and installs a seccomp-BPF filter that blocks dangerous syscalls like process_vm_readv, ptrace, and kernel module loading. As the creator noted in the HN discussion, this is defense in depth. The microVM is the real isolation boundary; seccomp is insurance.

The DX: Docker Muscle Memory, VM Isolation

One of Matchlock's smartest design decisions is its CLI interface. If you've ever typed docker run, you already know how to use Matchlock:

Any OCI image works. Want Ubuntu? --image ubuntu:latest. Need Python 3.12 with pip? --image python:3.12-alpine. The agent can install packages at runtime if you've allowed the package registry's domain. The workspace is shared via FUSE over vsock, so file access feels native without actually copying files into the VM. Every sandbox runs on a copy-on-write filesystem that vanishes when you're done.

For programmatic use, Matchlock ships SDKs in both Go and Python (PyPI: matchlock):

This means you can embed a sandboxed execution environment directly into your agent loop - launch a VM, exec commands, stream output, and tear it down, all programmatically. For anyone building their own coding agent (and given the current Cambrian explosion of agentic tools, that's a lot of people), this is significantly more ergonomic than wiring up Firecracker from scratch.

What the Hacker News thread revealed

The HN discussion (97 points, 39 comments at time of writing) was notably substantive - a rarity for security-adjacent launches. A few highlights worth unpacking:

On the limits of sandboxing. User DanMcInerney raised a valid point: sandboxing doesn't prevent prompt injection at the application layer. An email-reading agent that's been injected can still send your inbox to a malicious address - as long as the email API is allowlisted. Jingkai He (the creator) acknowledged this directly: "the unsafe tool call/HTTP request problem probably needs to be solved at a different layer." This is refreshingly honest. Matchlock doesn't pretend to solve everything; it solves the infrastructure layer and explicitly leaves the semantic layer for future work.

On Claude's built-in sandbox being insufficient. User arianvanp noted that Claude's built-in sandbox "gives read access to everything by default, so it's not deny-default." User ajb added that security-related issues in Claude Code's repo go unanswered and are automatically closed. This context is important - Matchlock exists partly because the vendor-provided solutions haven't been good enough.

On agents actively trying to escape. Perhaps the most chilling comment came from the creator himself: "From my firsthand experience, what the agent (Opus 4.6 with max thinking) will exploit without cap drops and seccomps is genuinely wild." This is not theoretical. An AI model, given sufficient reasoning capacity and access to a Linux system, will systematically probe for escape vectors. Matchlock's layered approach (VM boundary + seccomp + capability drops + network lockdown) is designed precisely for this reality.

On the useradd minimalist camp. One commenter suggested that a simple Linux user account is sufficient isolation. The response from Paxys is worth quoting: containers aren't a security boundary without extensive configuration (seccomp, AppArmor, gVisor), LXD VMs are QEMU-based and too heavy, and neither works on macOS. Matchlock's sweet spot is lightweight VM isolation that works the same on a Linux server and a MacBook.

The Competitive Landscape (It's Crowded)

Matchlock enters a space that's rapidly filling up. Let me map it out:

- E2B - Firecracker microVMs, clean SDK, AI-framework integrations. But: 24-hour session limit, no built-in network policies, cloud-hosted.

- Daytona - Fastest cold starts (sub-90ms claims), but uses Docker containers by default (weaker isolation).

- Microsandbox - Open-source, MCP-ready, self-hosted. Similar philosophy but different implementation.

- Modal - Python-centric, massive autoscaling, gVisor. But: no BYOC, no on-prem.

- Northflank - Enterprise-grade, multiple isolation options (Kata, gVisor, Firecracker), 2M+ workloads/month. Full platform, not just sandboxing.

Where does Matchlock fit? It's the self-hosted, developer-first, cross-platform option. No cloud dependency, no SaaS pricing, no 24-hour limits. Install via Homebrew, run locally, done. The tradeoff is obvious: you don't get the managed infrastructure, auto-scaling, or polished dashboards. But if your use case is "I want to run claude --dangerously-skip-permissions safely on my MacBook," - Matchlock is arguably the best answer currently available.

A Few Things I'd Like to See

The project is young (v0.1.6, 132 commits, 2 contributors as of this writing), and there's room to grow:

MCP integration. Given that Matchlock's creator also builds Kodelet (an agentic SWE CLI) and Opsmate (an AI SRE assistant), I'd expect MCP server support to land eventually. Exposing the sandbox lifecycle as MCP tools would make Matchlock composable with any MCP-compatible agent.

Filesystem policies. The README mentions filesystem controls as WIP. Once the agent can read your entire workspace via the FUSE mount, there's a data exfiltration vector through the allowed API channels. Per-file or per-directory access policies would close this gap.

Observability. Logging and auditing of what the agent actually did inside the sandbox. For enterprise adoption, you'd want a full audit trail - every command executed, every network request attempted (including blocked ones), every file accessed.

Benchmark data. Boot times, memory overhead per VM, and maximum concurrent sandboxes. The README claims sub-second boot, but concrete numbers across hardware configurations would help with adoption decisions.

Conclusions: The Right Tool for a Real Problem

Matchlock solves a genuine, immediate problem - and it solves it at the right layer. Instead of trying to make agents smarter about security (which is a losing game against prompt injection), it makes the environment physically incapable of leaking secrets or reaching unauthorized endpoints. The architecture is sound: VM isolation for the blast radius, network interception for egress control, MITM proxy for secret scoping. The DX is excellent: Docker-like CLI, OCI compatibility, cross-platform, programmable SDKs.

Is it the complete solution to AI agent security? No - and it doesn't claim to be. The semantic layer (knowing what the agent should do vs. what it actually does) is a problem for another tool. But as a foundation - as the "step zero" that one HN commenter called it - Matchlock is exactly what the ecosystem needs right now.

The fact that Jingkai He also builds the tools that need sandboxing (Kodelet, Opsmate) gives me confidence that the design decisions are grounded in real-world pain. This isn't a security researcher's thought experiment; it's a practitioner's response to watching Opus 4.6 actively try to break out of an insufficiently hardened environment.

A well-deserved GitHub star from me 😉

Matchlock is available at github.com/jingkaihe/matchlock. Install via brew tap jingkaihe/essentials && brew install matchlock. Python SDK: pip install matchlock.

PS: And speaking of agent sandboxing - it's worth mentioning that SoftwareMill (part of VirtusLab Group, so yes, I'm disclosing a potential bias 😄) published Sandcat - a tool that targets exactly the same problem as Matchlock, but from a completely different angle.

Where Matchlock bets on microVMs (Firecracker/Virtualization.framework) and gives you hardware-level isolation with a separate kernel, Sandcat goes the dev containers route - all traffic routed through a transparent mitmproxy via WireGuard, with an analogous secret substitution mechanism and network policy engine. The isolation is weaker (container vs VM), but in return, you get native VS Code integration and a full dev container workflow, which in day-to-day work can be a serious convenience.

If you're looking for sandboxing for everyday work with agents, test both and let me know which approach fits your workflow better.